They Laughed at Fortran — Until It Took Us to the Moon

Fortran, the world’s oldest high-level programming language, still outperforms Python in math-heavy computing. Discover its untold story and legacy.

TECH TALES

8/31/20253 min read

In the 1950s, computers were monstrous machines, and programming them was even scarier. Writing code meant working with 1s, 0s, or cryptic assembly instructions. Every program took weeks, even months, to write. Then came Fortran in 1957 — the first high-level programming language that changed everything.

But behind its creation lies a story of frustration, skepticism, and one rebellious IBM engineer who didn’t want to suffer through assembly code anymore.

Before Fortran, programming was a tedious and grueling task, dominated by endless strings of machine code. Scientists often found themselves spending more time wrestling with the computer than actually conducting experiments or solving problems. Even powerful machines like the IBM 704 were nearly impossible for anyone but experts to operate efficiently. The need for a breakthrough was urgent—something that could make computers accessible, efficient, and practical for real scientific work.

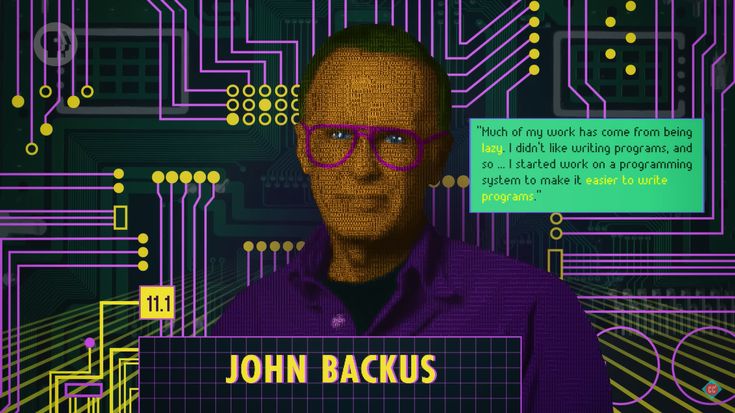

John Backus and the Birth of Fortran

John Backus, a mathematician at IBM, openly admitted he hated programming in assembly. In 1953, he proposed something radical:

“What if we could write code like math formulas, and a compiler does the dirty work?”

His bosses hesitated but gave him a small team. And so, the Fortran project was born.

The programming community didn’t take John Backus’s idea seriously at first. Many scoffed at the notion of a high-level language, insisting that compilers could never be efficient enough. Critics argued that scientists would never trust a machine to translate their formulas, and some even dismissed the entire project as a waste of IBM’s resources. Inside IBM itself, there was genuine fear that if the project failed, it could damage the company’s reputation. With so much doubt surrounding them, Backus and his team carried the weight of enormous pressure.

The challenge ahead was daunting: their compiler had to make Fortran programs run just as fast as, if not faster than, hand-written assembly. For three long years, the team painstakingly crafted optimizations, pushing the IBM 704 to its limits. They fine-tuned every detail, determined to prove the skeptics wrong. When they were done, the result was a compiler spanning 25,000 lines of code—at the time, one of the most complex software systems ever built.

1957 – Fortran Is Born

When Fortran finally launched in 1957, it stunned everyone. Against all expectations, the programs it produced ran just as fast—sometimes even faster—than carefully hand-written assembly. Suddenly, scientists who once spent weeks coding could accomplish the same work in just a few hours. Adoption spread like wildfire. Physicists, engineers, mathematicians, and even NASA quickly embraced the new language.

In fact, Fortran became a cornerstone of NASA’s early space missions. From simulating rocket trajectories to crunching the complex mathematics behind orbital mechanics, it gave scientists the speed and reliability they needed to dream bigger. The Apollo program, which carried humans to the Moon, relied heavily on Fortran for simulations, spacecraft design, and mission planning. Behind the astronauts, rockets, and moon landings was a language born from frustration at IBM.

But Fortran’s rise wasn’t without controversy. Traditional programmers clung to assembly, insisting that trusting a compiler was reckless. Some even mocked Fortran as a “toy language” unfit for serious work. Yet, as Fortran quietly powered nuclear research, weather forecasting, and the space race, those critics were forced to swallow their words. What began as a risky experiment soon proved to be the very foundation of modern scientific computing.

Legacy of Fortran

Fortran’s impact didn’t end with its launch—it went on to shape the very foundations of modern programming. In 1966, it became the first programming language to be standardized by ANSI, ensuring that Fortran code could run across different machines. That move made it truly portable, something unheard of at the time. Remarkably, Fortran is still alive today, with its most recent standard, Fortran 2018, proving that the language has adapted and endured for over six decades. It continues to dominate fields where raw number-crunching is essential: supercomputing, physics, climate modelling, fluid dynamics, and more. Some of the world’s fastest supercomputers still rely heavily on Fortran because of its unmatched efficiency in handling mathematical computations.

John Backus himself once quipped:

“Much of my work came from being lazy. I didn’t like writing programs, so I invented easier ways to do it.”

That “laziness” sparked a revolution, giving birth to modern programming and forever changing the way humans communicate with machines.

Fortran’s story isn’t just about a programming language—it’s about how frustration, doubt, and even a bit of laziness can spark revolutions that shape the future. More than six decades later, Fortran still powers the world’s biggest scientific challenges, reminding us that innovation can come from the most unexpected places. But what do you think? Does Fortran still deserve its place in today’s tech world, or should it finally retire as a legend of the past? Share your thoughts below—I’d love to hear your perspective.